The PGIC Map and Lot-Pricing Schedule: How Pennington Gap Was Marketed, Laid Out.

- Jan 31

- 6 min read

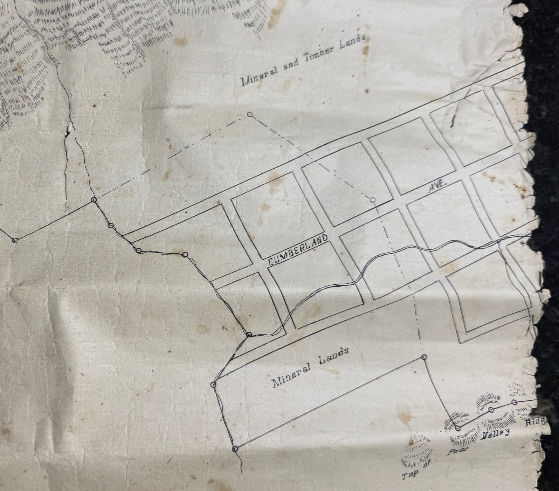

The drawing, pictured herein, is a surviving portion of the Pennington Gap Improvement Company (PGIC) Land Purchase map prepared for E.W. Pennington. The person responsible for preparing the map did not identify himself, nor has a date of preparation been located. It was found in the estate papers of William Hamblin Russell II of Sugar Run Road and gifted to the Lee County Historical & Genealogical Society in October 2025 by his son, Michael Russell.

This gift matters because it preserves something we rarely see: a practical tool used to lay out, market, and price lots during Pennington Gap’s earliest boom years. PGIC was organized in 1890, and Pennington Gap was incorporated soon afterward (approved February 15, 1892). The donated map fragment and its reverse-side pricing schedule help us see how the town’s growth was managed in real time, especially when paired with first-hand newspaper accounts from 1891.

The Pennington family owned vast lands along the North Fork of the Powell River as it flows through the Cumberland Mountains near the “Hanging Rock.” In the mid-1800's they developed a grist mill and operated a foundry using locally sourced iron ore from the Poor Valley Ridge. With the Louisville & Nashville Railroad pushing through southwestern Virginia, landowners and investors were drawn to develop towns at key locations. E.W. Pennington, an attorney and landowner, looked toward development near the river junction and the L&N line through Lee County.

PGIC’s principal officers were H.C. Joslyn, President, and E.W. Pennington, Attorney-in-fact. Pennington and Joslyn organized the company on March 21, 1890, and later recorded Pennington’s authority as the corporation’s authorized agent. As Attorney-in-fact, Pennington could convey company land, set terms, sign deeds, receive payments, issue receipts or releases, collect debts, and take practical steps to market and sell land, legally binding the company in property transactions. In plain terms: he was empowered to act as PGIC’s land agent.

What the donated map shows fits that purpose. The front carries a bold legend describing PGIC’s “land purchase” in Lee County, emphasizing mineral lands, town lots already laid off, and additional grounds “subject to such division.” The surviving portion depicts the Top of Stone (or Cumberland) Mountain, mineral and timber lands, a blocked area of uniform lots along Cumberland Avenue, and the Top of Poor Valley Ridge. It presents Pennington Gap as both a town site and a resource landscape.

The reverse is even more revealing: a pricing schedule used to determine lot cost by size. The chart is laid out in major rows and columns and subdivided into smaller grids representing lot dimensions, small lots such as 10×10, 10×20, and 10×30, scaling up to larger combinations such as 90×40 and 90×50. Numbers within each block appear to assign values for irregular sizes or for grouping lots together. In other words, the map wasn’t only descriptive; it was operational, part of a system for selling lots quickly and consistently.

That is exactly how Pennington Gap was being promoted in early 1891. A two-column advertisement (below) in the Bristol Courier _ April 14, 1891 pitched Pennington’s Gap as a healthy, high, dry location with pure spring water and outstanding Cumberland scenery. It emphasized nearby coal, iron, limestone, and timber, described the Gap as a natural outlet for the Kentucky coalfields, and then stated plainly that the town property belonged to PGIC, which was grading streets and putting down waterworks.

Most importantly for understanding the donated schedule, the ad noted that PGIC offered more than 400 lots for sale through company agents “at scheduled prices,” ranging from $50 to $300. Terms were one-third cash down with the balance in one and two years (with interest). The ad also included a condition that no liquor would be sold by the purchaser within three years from October 6, 1890, and it directed inquiries to “Ed. W. Pennington, Gen’l Manager,” and to “Robt. C. Cox, Office Title Bank, Bristol.” The phrase “scheduled prices” is no longer abstract when you can point to a surviving schedule, one that appears designed to apply such pricing in practice.

By late July 1891, the Big Stone Post published what reads like a rapid-fire progress report from the ground. In a letter dated July 29, the writer claimed that “two months ago the population of this place was six, now we claim 250 souls.” Building was active, with more than two dozen houses going up, and lots being sold daily to outside investors, including some Harlan County, Kentucky people coming across the mountain to trade. The depot agent, Asa Johnson, was putting up a substantial building said to cost about $3,000. (writer's note: Hotel Johnson?)

The same letter reports that PGIC’s office building was nearly completed, with manager E.W. Pennington “preparing to move in”, along with agents of the New York & Southern Lumber Company, making it their headquarters. Streets were being graded by contractors with 40 to 50 hands at work. “Piping the town” for pure spring water from the nearby mountain was expected to be completed soon. New enterprises were already being discussed: a planing mill and furniture factory to employ about 50 hands. Then comes a single line that hints at how far outside attention reached: “Messrs. Mallette & Nicoll, of Brooklyn, N.Y., were here last week.”

A follow-up letter dated July 30 adds more detail that helps readers “locate” this growth. Judge H.J. Morgan planned to open a bank in a few weeks, with stationery, safe, and materials being prepared; it would be located on Kentucky Avenue, described as one of the most central locations in town. PGIC had purchased the Turner farm (140 acres) for future development. Sales continued, averaging about $200 per day for the month, “certainly a good showing these times.” The Russell farm was being subdivided into lots about 75 to 100 feet, described as a continuation of Morgan Avenue and Davis Street. The New York & Southern Lumber Company had built a shed on its log yard, with “great activity” prevailing. And the railroad planned to put in four sidetracks the next month, “preparatory to the beginning of the railroad into the Pocket country.”

Two weeks later, the Big Stone Post’s August 14 report shows a town still building hard, but now with more institutions and infrastructure coming into focus. A.B. Kesterson of the Cumberland Gap Bank visited and promised to open a bank in the near future, so the town expected two financial institutions. Building continued briskly, with foundations laid daily and “not a vacant building in town.” The lumber economy remained strong: logs and lumber wagons coming in daily, shipments of lumber, logs, staves, and bark staying active. The article named Sam Duff, agent for Kilbourn Bros. of Big Stone Gap, preparing large numbers of white oak staves for market, principally intended for Philadelphia.

The August report also confirms major projects: a “great hominy and roller flour mill” to start soon under a contract between PGIC and George W. Gaines; a saw and planing mill being built by Hale & Co.; and commercial buildings rising, Johns & Slemp putting up a building on Joslyn Avenue for store purposes, W.P. Wood putting up a fine new store, and Fred Stickley preparing lumber for a dwelling house. Streets appear again as a timeline of growth: grading on Morgan and Joslyn avenues completed, work to start next on Kentucky Avenue, and the bridge on Morgan Avenue expected to be completed that week.

One detail in the August report also echoes the Bristol Courier’s no-liquor condition: Sheriff Chas. Flanery arrested Frank Mulvey for selling whiskey, and the report describes the arrest as tense enough that the sheriff fired a shot to compel surrender before the prisoner was carried to Jonesville. Whatever the legal authority behind it, the newspaper shows that controlling liquor sales was not merely a line in an advertisement, it was part of the town’s early public order.

Read together, the donated map fragment, its pricing schedule, and the 1891 newspaper accounts let us see the full early-development picture: a company assembling and presenting land; lots offered at “scheduled prices” under defined terms; streets graded, bridges and waterworks underway; businesses and mills planned or rising; banks promised; railroad sidetracks added; shipments moving; and outside investors visiting quickly enough that newspapers documented it week by week.

The Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society extends its sincere gratitude to the Russell family for preserving and donating this rare glimpse into the early years of Pennington Gap. We welcome questions, corrections, and additional information from readers.

Research and text by Ken Roddenberry (LCHGS). Edited with assistance from OpenAI’s ChatGPT for clarity and background context. Any errors remain the author’s.

.jpg)

Comments